Truce of the Discoverers

Download this chapter (PDF -171 Ko)

(If you find out « Mômmanh », « existence », « need of existence », please go to chapiter 2 to learn more...)

I had already taken the plane once: I had offered myself that luxury to come back home more quickly from Algiers, at the time of my “liberation”. As for Jeanne, it was her first trip by air and she hung on to my arm, forcing her nails in my skin, to elude her fear. I feel the same type of fear in the car when I am not at the wheel and I don't trust the driver fully.

The plane was a DC 6, a plane with propellers which would soon end in a museum. We made a first stop at Bordeaux, and then darkness enveloped us. While we were flying, it appeared that, the Pyrenees, Spain, Morocco, the desert, were equally shrouded in the night, at first I was playing the role with pleasure, then with a growing irritation, my role of a magic protector. But I ended by giving up.

Since the “rumbling” of the engines, for which the hostess showed her gracious boredom, was obstinately regular, and since the air was bringing us a lot of attentions, without all those disrespectful shakings which other types of transport imposed upon us, the train, for example, since everything was so calm, I dosed off like a baby tired out by a tender lullaby. During that time, Jeanne struggled in an agony of fear.

But it was written that I would not have slept that night. In fact, the loud-speakers announced calmly: “You are asked to fasten your seat belts, because we are going to fly across a turbulent zone.” And the place started to jolt on its air cushions, like a car hurtling down without brakes along the slope of a mountain. From the windows, we could see, from time to time, a furious white flash tearing up the night. Also we happened to drop like an elevator suddenly falling down. After a long time, too long, that stopped: we were saved for that time, but a new fall did not take long to arrive. It is probable that after that, we gained altitude, because we never bumped against anything solid. The commander on board had done well to have us fastened, because my Jeanne, so impulsive, would have rushed to the door to leave that place. She still huddled herself to me in her distress, but the raging elements were the indications of my imposture: no, I was not the good genius she expected. I looked to see how our human brothers were behaving, the other passengers who I presume to be old experienced colonials.

The majority seemed to feel no fear; some were reading, others chatted quietly. I was then half assured enough in any case to take up my role of male protector.

Then the air and the skies became calm again. Jeanne gripped tenderly to me and we felt that love was enwrapping us. “Stupid happy ones.” you would say? Oh no! Her hot coat seemed too solid to be woven only with illusions.

Jeanne told me that we stopped at Bamako, when it was still night time, but I don't have any recollections of it. While the passengers and the freight were moving, we stayed in the plane. It is there, always in advance therefore, that my better feminine half had her first taste of Africa: it was hot, acrid and rich, well lined with a quantity of strong scents, loose, which were wrangling vigorously. Curious of the slightest new sensation, my Jeanne was all excited. But already the plane had taken off heavily on the runway that she gripped with all her nails to my arms. Jeanne told me that we stopped at Bamako, when it was still night time, but I don't have any recollections of it. While the passengers and the freight were moving, we stayed in the plane. It is there, always in advance therefore, that my better feminine half had her first taste of Africa: it was hot, acrid and rich, well lined with a quantity of strong scents, loose, which were wrangling vigorously. Curious of the slightest new sensation, my Jeanne was all excited. But already the plane had taken off heavily on the runway that she gripped with all her nails to my arms.

Soon, it was daytime, clearly and rapidly, as it does in the tropics. Then, a portion of Africa came to our sight. It was bizarre and disappointing. We saw a reddish land filled with small green flashy bits which resembled vaguely the artichokes. The villages appeared like fragile toys placed anyhow on that desolate land. What I recognised later on as fields were like chicken spurs which must have scratched at random to look for grain. There were no men, since we could not see them at that distance. I asked myself besides, if they existed and, in the affirmative, where on earth could they find anything to survive on! Here, and there, rare clear stains. Vaguely shining, resembling puddles of water. The most frequent, the red vineyard of the laterite was the dominant tonality and that which was vaguely green had to be vegetation, appeared like messy stuff. However no, we had not arrived on the moon.

We landed at the airport of Ouagadougou. The tyres bounced once on the asphalt before rolling very steadily like those of a car.

We were alive and in good health. Hurray!

At the exit from the plane, we entered into a bath of heat rather clammy: the first kiss of Africa; it was up to us to accept or to go back. The director of my school was there. He was, and for some more years, still a Frenchman. He welcomed us in the same way as the exiles would welcome their own fellow countryman who brings them like a whiff of fresh air, some food of which their nation had given them the taste and who, owing to the absence, creates a pressing desire which one calls “home sickness”. Like this, abroad, one sees the French behaving themselves in a bizarre manner: an ambassador looking for the company of a bricklayer, for example, or a well driller learning bridge or tennis to please his friend the lawyer.

The colleague director made us get into his official Deudeuch.

To start with, we crossed a great town populated exclusively by blacks: a novelty, but not truly a surprise.

The extreme poverty and the misery no longer, were not really the reasons for surprise: the press of the “Party” had announced it many times to us. It was, it stated, the consequence of “neo-colonialism”. Always the same story, in the background: a new episode of the “Struggle of the Classes”, that is to say the implacable combat which leads the rich to rob the poor. That war was the gangrene of humanity and it stretched, overcoming time, I mean “History”, and space, for the whole Earth to know. She would only end with the disappearance of the exploiting class, that of the rich, thanks to the collectivization of private enterprise. So, the human being will become naturally good and the false paradise of the next world, promised by all the religious, mystifies and swindlers, will be replaced by the true paradise installed in our good old World thanks to the Communists.

Why does the natural selection make of us beings of faith ?

Mômmanh made man in a way that he requires very solid pillars to rest his ideology on. They are first of all forged by a reflection as deep as possible. Afterwards, soaked in the acid of the faith, supposed to be from now on indestructible, they become dogmas.

Even faith is a gift of Mômmanh, not intentional, because she never makes a plan, but an empiric choice, because she resounds what she herself proves.

The dogma of the “Struggle of the Classes” was supposed to explain nearly integrally the faults of human nature and the misfortunes of history.

I was quite ready to admit that explanation, but first I had to understand it and, for that, question the fact until the moment when I would be convinced of its justice. Like this my insatiable thirst to master everything by thought required it, the painful passion of which you know that it had its good side: very useful when I manage to control it, it became, alas, like all passions, too dangerous when she wrapped like a mad mare, leading me, clinging to her neck, deadly pale and speechless with fear.

It was not the first time that I tried to control the reliability of a dogma of the “Party”. Here you are that other example emerges from the marshes of my memory. It was some years earlier, during the War of Algiers and, of course, the “Party” explained that it was necessary to see there, simply an episode of the “Struggle of the Classes”. So I had the possibility to follow my studies and to remain in reprieve, in the shelter until that vile business was over: instead of that, and in spite of the fact that I fear fire shots as well as stabbings, I “interrupted” my reprieve and I enrolled as a volunteer for my military service in Algiers; I wished to see with my own eyes that sinister ruling class on the verge of accomplishing its black outlines, but I never managed to distinguish it clearly. A new crack had formed itself in the shell of my faith which was all new.

But it took much more in order for it to be torn apart completely. Besides, she had been scratched after the beginning, when I had refused to admit that “Religion is the opium of the people”: I could not consider the good man who was my parish priest like a drug pusher, neither those who had died for their faith as dealers or drug addicts.

That time still, I was going to dedicate long years to strive to understand how the neo-colonialists caused the misery of one third of the world so that they indulged in it. The longed for moment of that revelation was never to come. I had to continue to search until the day, when having reached the intuition of a better explanation of history, I felt definitely in heresy. In the meantime, my faith continued to crack little by little.

The director was a pleasant man and a willing gossiper. He interrupted his flow of words after we assailed him with our questions: on hearing how we were anxious to discover our new land, he did his very best to satisfy us.

In the mounting heat and the harsh, merciless, light of the tropics, we crossed the capital. Even the Deudeuch, which should have been familiar, seemed strange here: stained with red mud, the seats coated with doubtful material agglutinated with a fatty substance, truly based on abundant perspiration, the rims dented, the tyres gashed with worrying scars, the doors, the panes and the different components of the body takes apart, as if they had been put down and then mounted in a hurry, without any care. That means of transport seemed more terrifying to us than the plane but there was such anarchy in the circulation that it was impossible to drive fast: then, when we were within the limits of the capital which, decidedly I could not call city without degrading that word, I felt safe.

My Jeanne and I, we are untirably curious of anything one can find on that land, and even beyond: that is one of the reasons for which we demand the right to live one thousand years. But it seems that that request, however modest, is senseless; so it is better if we leave it up to others, to those unknown of the future, the pleasure to discover other existential foods, on earth as well as over there in heaven. I wish that we can trust them! In all manners, we do not have the choice. So, may they know this?

No country is delivered entirely at first go.

Of all the aptitudes to be seen, to be heard, to be understood, to be tasted... of which Mômmanh has gifted man, we only developed one part: that which our cultural matrix of the Western France has worked. The rest, due to its rejection, has lost nearly all its vitality. However, some of the elements are still capable of being reborn, no matter how little they stimulate them, trying to adopt themselves to a new world, for example. But, to succeed in this metamorphosis it takes effort and time.

Think of a good wine, produced in a territory and of a culture: it is rare, isn't it so, that you can, after the first glass, taste all the other qualities; it often happens even, that the neophyte judges it badly and he prefers a sparkling “Coca Cola”. It is necessary that you have tasted it many times, preferably in the company of good friends, so that you become sensible to his multiple components, inventions of the living nature offered to whoever has not lost the taste of life. Ah well, the discovery of a country necessitates, at least, an even patient initiation and, surely, at the end of those efforts to open for you new flavours, after those long engagements, he is not sure that the nuptials will take place.

The country where you step for the first time does not only offer qualities to discover: it will be too beautiful and even, probably, annoying. It is necessary also to become conscious of its faults and learn to live with them. Among the Frenchmen of Africa, the ancestors, our initiators, experimented this by means of a parable.

A Frenchman who had just arrived made his first round. He discovers a fly in his glass: by reaction, he throws the good whisky and has his glass washed. A few months later, there are two flies which are fighting in his whisky: he satisfies himself by removing them before drinking. At the end of some years, he has become an elder. It is like this that one begins to understand: when there are no flies in his glass, he catches at least one to put it there.

Finally, there are always, in a discovery of a country, some linked novelties which allow themselves to be appreciated soon : the flavour of a fruit like the mango, for example, or the passionate violence of a landscape, the sweetness of the light, the beauty of women, the surrounding cheerfulness... and what else still ?

At first, that strange capital impressed us. And it was good!... But how do I make it clear to you to feel the effects?

Everything was new, as if we had changed planet. Poor, most often, spy latched, destitute, but new! The trees, the streets, the houses, the clothes, the people, and even the birds... But yes!

There you are! As regards that, we discovered, how a note of welcome humour, those hideous volatiles with a featherless neck, with their head covered with repulsive rolls of fat evoking bad meat, those big birds unseemingly like resonant farts in a worldly gathering, those poor vultures badly loved whose plumage seemed dirty, as if they had fallen in the waste. Besides, without any surprise, we learned that they are big consumers of rubbish, voluntary dustmen nicknamed vultures, those unlucky benefactors of humanity who have drawn out unlucky numbers in the great lottery of evolution. The chauffer-director informed us that the abattoirs of Ouagadougou were their general quarters. There you are! As regards that, we discovered, how a note of welcome humour, those hideous volatiles with a featherless neck, with their head covered with repulsive rolls of fat evoking bad meat, those big birds unseemingly like resonant farts in a worldly gathering, those poor vultures badly loved whose plumage seemed dirty, as if they had fallen in the waste. Besides, without any surprise, we learned that they are big consumers of rubbish, voluntary dustmen nicknamed vultures, those unlucky benefactors of humanity who have drawn out unlucky numbers in the great lottery of evolution. The chauffer-director informed us that the abattoirs of Ouagadougou were their general quarters.

A lot of women went about with their breasts showing, without provoking the slightest embarrassment, it seemed. Tied to their mother's back, some babies, even they black, nodded with their head in all directions, at the will of the maternal movements. There were old lorries that we had not seen elsewhere, except in the films about the 14-18 War, and which seemed to have survived a bombardment; they carried enormous and very high loads of wood, inclined to such a point that it seemed it was going to fall: at one moment I asked myself seriously if the laws of weight were, different, in this country.

The girls and the women carried boldly all sorts of things in equilibrium on their head: some paunchy jars, bundles of sticks, big basins full of lively colours, some small tables which they would have classified as made by some children and which served as stalls to the merchantmen and merchantwomen; loaded like this, they kept on straight, chest in front like the bow of a caravel, and they advanced while swaying their hips as much as necessary, but at the same time with a certain grace and a lot of ease.

It seemed that that daily exercise made them carry their head in a haughty manner. Still young, it was all that was left of their beauty: their conditions of life and their physical works were so hard that at the age of thirty they seemed more than sixty years of age.

The men, themselves did not carry anything on their head: their means of transport and locomotion was the bike, of which I learned later that they called it “iron horse”, heavy and solid bike whose rack would have had to bear the weight of a blacksmith's anvil. They carried four things, sometimes packed in rags, or tied up by means of a rough creeper; it happened that their load had the appearance of a shaky grotesque scaffolding and made up of ill-assorted and very humble goods: clusters of fighting chicks, their heads bowed down, faggots, some armfuls of fair calabashes, - those curious recipients of all shapes which resembled the skin of a pumpkin hard as wood -, boxes of small goods, sacks of grains, boxes of vegetables, machetes or some other quite modest tool, narrow rollers of thick cotton cloth woven in the village by the owner of the bike...

The women, the bikes and the old lorries were not the only means of transport: there were also processions of little metal carts equipped with tyres, pulled by donkeys. Even if their assembly was done in that place, they represented well the industrial products of our western world, above all when one compared them to the local artisan crafts: some shapeless bows, some arrows in rough wood armed with a point of forged iron without symmetry, coarse potteries decorated with motifs which resembled designs made by children, white shapeless clothes called boubous and made of straight strips of country cotton sown ones to the others, small curved legged furniture which insulted the law of geometry and equilibrium, some sandals made of straps of old tyres cut by a knife, a derisory luxury of the citizens who did not want to walk barefoot in order not to be mistaken with the peasants who were still backwards...

All those items were made entirely by hand, without precise measurements and with techniques - I must say - primitive: how many times do we meet in everyday use, like the flat stone to crush the cereals, or still the rustic weaving job of the peasants, the same objects that one would see in museums about prehistory!

The use of the wheel - No! I do not exaggerate! - The use of the wheel, was therefore, very recent, and it limited itself to the imported items. After a century of colonisation, the Burkinabés had not yet decided to make some of them themselves: perhaps it seemed derisory to want to make by hand and with great difficulty what the industry made so easily?

Which is the basis of human existence in Burkina Faso?

In that country where about ten different races lived having each its own language and culture, the civilizations had not developed maths, neither science. Therefore technology was equally so: prehistoric. But their thought, following different ways from ours had certainly discovered other food to calm the insatiable hunger of existence which leads us all. Yes, what was then the contribution of those races to the patrimony of humanity?

At Burkina Faso like in any other country of the World, men carry on with their life with what nature proposes to them. Here like elsewhere, the gifts of Mômmanh are for many in the colours and in the tastes which the human existence will take up. Now, besides a very hot sun and a suitable lot of endemic tropical illnesses, nature has not offered big things to the Burkinabés, not many big consumable things, I mean.

When the peasants had earned enough to make a generous meal every day without meat they estimated that their business was not bad. Moreover, the country does not receive practically any profitable resource. No fuel, neither hydroelectricity, nor any other energy source at a bargain price. No diamonds, neither copper, not even iron, no ore if not a pinch of gold which serves only to make one dream: one has not seen, I don't know in which year, a sparked-off rumour which I believed without foundation, or a fleeting rush for gold, in the north of the country, like a bite in the hollow of a hungry shark.

What is animism? How did animism, polytheism, monotheism, and atheism link themselves.

So, Mômmanh did not show herself generous towards the Burkinabés. But didn't she show herself equally stingy, or quite so, with regards to the Japanese?

Let us see the other group of the existential resources: the culture. She is just as performing as the closest knowledge of the scientific rigour is understood. The culture of a nation is acquired thanks to the multiple exchanges between the races, associated with good conditions for the studies: the time and the material means. Ah well, those cultural ferments had been very smartly attributed to the dowry of black Africa.

The basic ideology is an endorsement. It is prehistoric: it is animism.

In fact, the ideology rests on the global explanation of the world which seems the most plausible. In the prehistoric age, the first men believed that all beings, and even everything, with the like of man, were governed by minds: they had just invented animism.

Later on, in the light of the new knowledge, some other men judged unlikely the existence of intellects. Then, what?... And they invented polytheism, like the Greeks. Later on, in the light of the new knowledge, some other men judged unlikely the existence of intellects. Then, what?... And they invented polytheism, like the Greeks.

Every race having its own, the gods were millions and millions. Later on still, that immense crowd of divinities which contradicted and squabbled all over the world seemed too incoherent: one invented monotheism.

Then atheism came...

Those beliefs are our blind dog that explores the immensity of the real and gets out of it the best parts. He who served like this as guide to the Burkinabés was, there still, a living fossil, quite close to animism.

The animists believed that, everything like the man of flesh is inhabited by an immaterial soul: his intellect. The whole of nature has been created by some intellects, she is governed by some intellects, and she is inhabited by a multitude of intellects.

In the lion's flesh there is the intellect of a lion, in the water of the river there is the intellect of the river, and so on and so forth. In order to obtain what one wants out of nature, it is necessary to call the power of the intellects.

I discovered that belief by chance, one day when all my students refused to cut the long grass on the ground which would have been their garden. They were however very motivated for that work. They had all improvised, with more or less luck, some excuses the sum of which was incredible: weddings, funerals, collective work, market, administrative summoning... There was also a false bandage.

“- What have I done to you, that you treat me like such an idiot? Why that insult?

And one of them dared to reveal the true reason of their attitude.

“- It is the god, Mister. He is in the grass. If one cuts it, he is going g to be angry.

- Very angry, indeed! Let's go one step forward. There is going to be a great misfortune.

- You see, sir, the grass is green: the god is there, for sure!

- Mister, wait for some days only. When the grass is quite dry, the god has left. Then one cuts the grass... calmly.”

Evidently, the scientific discoveries are hardly favourable to such beliefs: when one looks for the evil intellect which is responsible for an illness, the chances are reduced to discover the true guilty one, a germ, for example.

Having said that, and in spite of everything, when one follows a different way, and he is completely in the wrong, one must discover different things. Therefore, while following the roads traced by the animist's creed, the Burkinabés must have done some original discoveries. It is true, but I only manage to see the most evident. I think first of all about the virtuosity of their drummers and their dancers for whom their art seemed so easy and essential like respiration for me. I think also of their broad smile which is not of politeness like it is for the Asians, but simple good mood, and which reigns like the sun in the middle of their extreme poverty. I cannot discover the secret of that smile. Having said that, and in spite of everything, when one follows a different way, and he is completely in the wrong, one must discover different things. Therefore, while following the roads traced by the animist's creed, the Burkinabés must have done some original discoveries. It is true, but I only manage to see the most evident. I think first of all about the virtuosity of their drummers and their dancers for whom their art seemed so easy and essential like respiration for me. I think also of their broad smile which is not of politeness like it is for the Asians, but simple good mood, and which reigns like the sun in the middle of their extreme poverty. I cannot discover the secret of that smile.

I think also, and I should have started from there, of the quality of the Burkinabian welcome. My Jeanne, our children and myself, we have been very happy in that country and when we were not, out hosts were not happy at all. And however, their way of living and their mental universe were so distant from ours that only the really strange extraterrestrial could be like that.

As regards that, I cannot resist the temptation to relate an anecdote to you.

During an excursion in the bush with my friends, we had to spend the night in a remote village where the children had never seen any whites yet. And they were numerous; those little blacks with big eyes open wide who pressed around our modest encampment. The most daring touched us. They observed everything: cars, camp beds, cool boxes, luggages, all our things and even the slightest of our gestures, the slightest of our actions. We were like animals in a zoo.

The evening was advancing, and we would have loved to sleep, but the children were always there and there was no sign which indicated their intention to respect our sleep and our privacy. We could not speak to them because none of them understood French. That evening there, we felt far, far, very far away from home.

It is then that the “Holy Spirit” descended on our friend Roger. In his beautiful Italian voice, he started to sing “I am going to see my Normandy again” and he started to teach that song to the children. Even they started to sing:

“I am going to see my Normandy again,

It is the country

Which gave me the day.”

After which, Roger mimed a sleepy man and, with gestures showed the children that they had to leave.

We spent a good night under the stars.

Let us come back to the works of the multiple cultures of that country: I was not capable of knowing if the other Burkinabe inventions are worthwhile or not. They pretend to have discovered a quantity of good recipes, in many domains, discoveries which our scornful attitude leads us to ignore completely. They could have some efficient local medicine; they know how to treat, in their own way, stress and some other complaints of the soul; they might even have some interesting techniques which they invented in the fields of agriculture and craftsmanship.

It is true that we were ill-prepared to discover the soul of black Africa.

We have seen that a culture is a living architecture and a complex outcome of a sum of apprenticeships. It is nearly as difficult to change culture as to change body to be born to another life. But that is not the only limitation in our aptitude to discover: we were oriented towards another aim: to bring “Civilization” to the poor blacks.

There exists a western ideology which wants to govern the world. One can summarise it to this: materialist science, democracy and human rights. At the times of our youth, in all the cultures of the world, but above all in ours, the western intellectuals dug up what our ideology judged as good. The product of that harvest was called: “Civilisation”. And France, in her ex-colonies, sent “overseas development workers” in charge of spreading it. There exists a western ideology which wants to govern the world. One can summarise it to this: materialist science, democracy and human rights. At the times of our youth, in all the cultures of the world, but above all in ours, the western intellectuals dug up what our ideology judged as good. The product of that harvest was called: “Civilisation”. And France, in her ex-colonies, sent “overseas development workers” in charge of spreading it.

We did not come to Burkina Faso to learn, but to teach “Civilisation”. That confinement in our ideology was a second obstacle in the discovery of the Burkinaby cultures

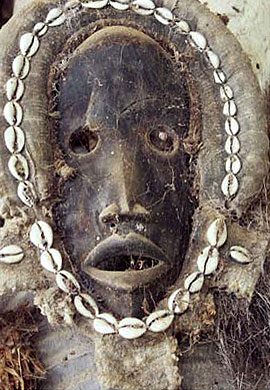

As regards the animist thought, at the time of our arrival in black Africa, we considered it twice as scornful. To start with, we ignored its existence as a thought. Afterwards, the curious rites which the colonialists had reported in the media, the grotesque disguise, the diabolic dances, the practices of the so-called magic, the beliefs in the supernatural beings supposed to live or possess such an individual, all that colonial folklore appeared to us like a mixture of superstitions born out of ancestral ignorance. “Civilisation” recognised as good only the negro art, essentially the masks and the dancing: all the rest was to be discarded...

Besides, all the old fashioned things would not take long to vanish. You know why: we had just arrived, especially myself the teacher, twice as enlightened by the glorious secular French school as well as the infallible Marxist thought!... Ah but!... Some others and I, we were going to lead those people to the road of knowledge and prosperity. The whole of Black Africa was going to rise up, surprising the world by all its feats.

“-Well! By the way, remind me where we had stopped. Speak more loudly because I am hard of hearing. How ?... Ah yes! Sure, it is up to me not to mislead myself, otherwise how can I guide you, my poor friend? Ah well, so be it! Sorry?... Who will come to do these digressions in a love story? - Ah well, it seems I have already said it to you. So, so much the worse if I repeat !...”

How is the loving orgasm the firework of two successful existences?

Two people, generally of complementary sexes, do all they can to succeed in their love, each one on his side until the moment of their meeting, the moment when they feel the desire to melt away their two existences. If they manage to grant themselves to each other, Mômmanh rewards them and fills them with joy.

Yes, I have already said it, but it is so good!

Ah well, it is still like this, for my Jeanne and myself, in spite of our advanced age and all the stupid things that we have done. Every night, when our bodies find themselves flesh against flesh, we feel warmth which has nothing in common with that of a radiator. No, even now, above all now, I will not exchange my well beloved for a steaming toddy and a hot water bottle.

Because that warmth, which we feel, is a current of pleasure which erases all our wounds, it is, I believe, the benevolent caress of Mômmanh, the applause of Mômmanh who encourages us like that to continue. Because that warmth, which we feel, is a current of pleasure which erases all our wounds, it is, I believe, the benevolent caress of Mômmanh, the applause of Mômmanh who encourages us like that to continue.

So, you see!... Since love is the triumph of existence, it is necessary that I relate to you our own. Without which, this novel will be a door on emptiness, like those kitsch postcards or two mannequins, doubtlessly naked in a shop, embracing in the middle of a heart of barley sugar, representing, it seems, the two lovers.

And all this does not tell me in which period of history we have arrived. Ah! Here we are, I am here.

We had just arrived at Ouagadougou. Our love seemed solid and however the game was far from won. But we ignored them.

In the meantime, we were surprised, intrigued, excited by all the novelties which that strange capital was offering us. Its call was literally aspiring us.

The pleasures revealed by expe rience and the pleasures still to be discovered.

For the little man who arrives at the light of the world, the call for pleasures as well as for life is still virgin of answers. So, everything is new, everything is full of emotions: the first time that a baby assists to the flight of a bird, the surprise is so good that he bursts out in laughter. Then our existential space is decorated at the same time that it is building itself up.

From now on, our look is attracted towards that which we have already had the opportunity to appreciate. Let us suppose that the first pear which I have tasted has been delicious: now, each time that the fruit appears in my surroundings, it captures my attention. Therefore, the discoveries become rarer and their emotional force diminishes.

However, if he has done even the slightest bit of safeguarding to his soul a big door open to novelties - And long live the currents of air!-, since the existential domain is so vast that we don't know the limits, life will bring us just the same and often some good surprises.

Here you are, that reminds me of that evening of my youth when I used to do the hitch-hiking on the route to Caen. A beautiful car stopped and I was very happy. The inside was very comfortable, the engine powerful and silent, the driver also master of his driving like a bouncing antelope is of its body. The route wormed its way into the green countryside towards the altitude of one side. It is just at the summit that the triumphant music exploded in my eyes, in my head, in my whole being, and I heard something telling me, internally: “Thanks, my God.”

What was happening then? Oh, nothing extraordinary; besides, the driver of the car did not see anything. All commonplace, there was a magnificent spectacle in the sky, orchestrated by the setting sun, a spectacle which was only given, it seems, only to me.

After that sumptuous evening, a couple of decades passed during which I have had from time to time the luck of winning at the tombola of existence some beautiful revelations: a song, a promenade in Provence, an explanation of a mystery of life,... and I know that others will come to add themselves even if that extends my reprieve to the slightest extent. But none of my discoveries, also important, could give me the immense pleasure which was granted to me that evening there: I was so hungry! And I was fulfilled.

Ah well, my Jeanne and I, we cultivate that same care to safeguard in our soul a big door open on the world and all that which could be found beyond. We are therefore very curious of all that which could be in the universe and it is joyful, because what use will it be to keep the door open if we do not invite anyone to come in.

Is our link the strongest? How come? In any case, nosing around everywhere in the world, not only in the country, but in the books, the spectacles, in the people's head, wherever we have the chance to discover something interesting: behold our common passion. And there is still that: the persons who right away seem the most unpleasant to us, they are those who believe they know everything, otherwise known, as those whose intellect is closed, blocked, we consider them public menace.

Here you are: it happens, and it is not rare happily enough, that the beauty of a woman tears me out from my speculations very often pointless. That beauty calls me, saying: “Refrain therefore from arriving at my level, stupid! Rather than wasting the time granted to you.” So, I look at it more attentively. If I see, as is frequently the case, that she has not got those big questioning eyes which always, without letting themselves go, will call the discoveries, so I have the feeling that that beauty is not alive, and she does not interest me anymore. If on the contrary, on sounding those big eyes, the look reflects a feminine's soul, I find an avid curiosity that she may be accompanied by that generous momentum which demands only to be filled with enthusiasm for all the beauties of the world, if I see a beautiful soul which will greet with a clear burst of laughter any motif of surprise, then I feel strongly attracted.

Therefore, my Jeanne and I, at any moment, we are anxious to receive a new flavour, an unknown melody, a previously unpublished architecture, a promising thought... For that joy of enriching existence, we are ready in the possible measure, to upset our routine.

And we only want those false ideas to make a screen between the reality and us, even if they are sacred. Because above all we look for a real world and, if possible, which lasts a long time. After our garden of discoveries, behold a second one which we cultivate together: that of knowledge.

When we have done the gardening well, Mômmanh offers love as a bonus.

All this to tell you, at the time of our arrival at Ouagadougou, since we were young conscious adults that they will never be at all mature, and that we share that beneficial gift of insatiable curiosity, our capability of amazement was still very strong. She was no longer as lively as a baby who tries to catch a pigeon: discovering with surprise that the animal flies, he shouts his pleasure and applauds that exploit of the bird. No! in the Deudeuch which was travelling along the roads of that bizarre capital of a new world, we did not clap our hands while uttering cries of surprise and our colleague director did not have to worry about our behaviours.

We at first crossed the poor quarters: enclosure which down there they call “concessions”, surrounded by earthen walls more or less destroyed by the rains; rectangular huts, equally earthen, with the undulated roof more or less rusty, resembling the roofs of our hangars and which, like the latter, evoked the crusts of the bad wounds on the face of the earth, round huts also, with thatched roofs, a little more worth; heaps of rubbish here, there; some big trees like lime trees, with abundant foliage of a very healthy green, touches of optimism about which they told us that they were mangoes which came from India and which produced delicious fruit; there were children everywhere some of whom were completely naked, the bodies sometimes covered in ash; raw-boned dogs, some chicks, some goats, some pigs, and even, it seemed to me, at the turning of some dusty road of red clay, a horse so thin that it seemed to be waiting for the end of the world, or still a strange animal called “zébu” and which resembled a cow, with big horns, with a ridiculous hump attached to his back, which hump jolted in such a grotesque manner like the breast of an old lady.

I was asking myself what could one do in those familiar enclosures called “concessions”.

Besides our healthy curiosity about which I have spoken, youth obliges, I was led by the desire to impress our acquaintances, which could not fail to be more and more numerous, at the time of our return to France. I imagined them, pampering at my approach: “Here you are. Have you seen who is there? It is Georges. But yes, one has surely spoken about him, Georges the African, he who knows Africa like his pocket. It is important to listen to what he relates: it is fascinating. He has seen everything, understood everything! With him you know everything about Africa and the black people. Unbeatable! And then, he does a sacred job, down there! Extraordinary!

With him, it is the whole continent which is going to change. Wait a couple of years... Oh! Leave some decades and you will see: Black Africa will impress us... There will be beautiful black women on the Champs-Elysées, statuesque bodies of course, but supple, sensual, mysterious... Do you see? And then, you will see African products everywhere: it will be like for the Japanese products, now. What's more as regards black dancing and music, there will be the fashion, the cinema, the painting, the science, the literature... It will be all new and formidable, you will see. There will be a new Einstein, all black. And when you want to go on a trip to the moon, you will embark perhaps on an African spacecraft...”

So?... Will you still say that my delirium was totally selfish?... I agree: I had a sacred layer all the same. However, after having cleaned myself as best as I could from the frenzy of that glory, I continued in spite of everything to hope that the dream of a prosperous and creative Africa would materialise itself.

Discover the secrets of Africa which were spread out to the big sun in the familiar enclosures called “concessions” ? It is not so easy to penetrate the intimacy of the black cultures, even if you are kindly invited. Bearing our way there, there were a good number of obstacles which we ignored, starting with the false ideas of which I have already spoken. Amongst our peoples, enormous differences in levels of life and culture constitute other barriers some of which are quite evident. Here are some samples. Discover the secrets of Africa which were spread out to the big sun in the familiar enclosures called “concessions” ? It is not so easy to penetrate the intimacy of the black cultures, even if you are kindly invited. Bearing our way there, there were a good number of obstacles which we ignored, starting with the false ideas of which I have already spoken. Amongst our peoples, enormous differences in levels of life and culture constitute other barriers some of which are quite evident. Here are some samples.

In our western countries, we take great care of hygiene and different precautions which guarantee approximately our life until an advanced age, and we are keen not to die before we have received, a minimum, of our quota of years. Ah well, the extreme poverty of the Burkinabés does not allow them these demands and they live in the company of death. At least, it was like this for a quarter of a century and, keeping into account the extremely slow progress in Black Africa, I do not believe that that aspect of human condition has changed much.

They exposed themselves to all sorts of illnesses and, in the majority of cases, they did not have the means to pay for efficient cures. To start with, the villagers, as well as certain citizens, drank unhealthy water. However the latter could not be more natural since, generally it came directly from a sort of pond which filled itself in the rainy season and which one called “small lake”. That water is inhabited by colonies of parasites of all sorts, they themselves being absolutely natural, and it was not treated neither boiled, nor filtered, nor rendered drinkable by any procedure. By drinking it, with a little luck, one could catch many infections some of which were mortal.

If that means failed, there were plenty of others like them to invite death to one's meal. Here is one of the most simple, reserved however to the inhabitants of the capital: tasting without precaution a tender lettuce which the gardener had regularly and with much care watered with water from an open sewer which our friends familiarly called it “Rio del Merdo”.

The climate seemed suitable for the rapid development of the viruses, germs, amoebas, worms and larvae of all sorts. A big number of microbes covet your body to cut beefsteaks and dig their caves there where their colonies will live. They attack by air, by land, by the way of water equally and they know very well how to use the flesh and other food full of parasites which got in the way like the Horse of Troy. Lovers of novelties, you have a lot of line ups of surprising exotic illnesses: the malaria which is well known, but also some amoebas, some bilharziasis, some filariasis, the worm of Guinea, the onchocercosis ... if an excess of novelties give you the vertigo, the generous Africa keeps equally at your disposition a good assortment of familiar illnesses: measles, meningitis, hepatitis, typhoid fever...

Here is an insight of ordinary conditions of hygiene in the countryside, which no one calls the bush, down there. Know that in the city, where nearly all the citizens have come recently from the bush, health is not protected in a better way.

Ah well! In the house of the Burkinabé peasants, the table service was very simple. On the dusty floor one sometimes put a woven straw mat, but that wasn't an imperative rule. All the family sat around, on the ground, and the only plate was placed in the centre. Each dipped into it with his hands until everything was eaten. As regards the water, I have already spoken about it. Not only was it the standard drink, but it served also to wash the food, the pots, the calabash and all the other kitchen utensils.

Taken for granted that all the invited had washed their hands, which did not take place, that same natural water bore their imprint. Taken for granted that all the invited had washed their hands, which did not take place, that same natural water bore their imprint.

You have understood: to accept to take part in a meal in one of those mysterious “concessions”, to accept would be only a mouthful of water or of that millet beer which they call “dolo”, it was as if you were going to receive the kiss of a plague victim.

Once I found no means which did not seem offensive to negotiate a refusal and I found myself sitting in a dusty place in the company of a peasant family. In the centre of the group in a big calabash, there was the plate of the day, which was supposed to be a delight: some “peas”!... Like everybody else, without even washing my hands, I pick-axed in the common calabash something which resembled chick peas; when I crunched them under my teeth something screeched which I took for sand grains contained in the earth which remained attached to the famous peas. That interpretation is a little credible but I could not check it. To make the things slide along as far as my stomach panicking, I could drink from another common calabash, some brimful glasses of the good dolo, evoking vaguely certain ciders of my childhood, but nonetheless very, very dubious. In fact, I am not at all authorised to describe the taste of those foods because fear prevents me from paying attention.

As soon as decorum allowed me, I moved away in the ochre dust and I took refuge in the hut which they had given me. I remained there till I found a remedy for the panic which had invaded me. That experience was free: no colony of parasites had installed itself in my body. Afterwards I always knew how to find the means to refuse that type of invitation and it was, I hope, without upsetting anyone.

How can the cultures understand each other without destroying each other?

Wasn't there already, an insurmountable barrier between the peoples and us? Ah well, no! In fact, the majority of the obstacles which I evoked, if not all, could be got over. But practically every time, you must put patience and tenacity into it.

In the general way, I think that we ourselves have erected those barriers laboriously during the struggle to live indefinitely. And the moment has come to lower them, those damned barriers, now that the human existence can express itself on a mondial scale. Men have to be capable to compare their respective ways of existence and to get a profit out from them, in the way in which the women can present themselves mutually and comment about their outfits, enriching like this their arsenal of seducers, without however flying in their feathers.

The ideologies are difficult to present and to discuss. To start with, the interlocutors must admit that they are not keeping back forcibly the truth, but that they are obeying their beliefs. Facing those who believe in intellects teachers of the universe, even we, the westerners, we must recognise that we believe in another explanation: matter barred of all the intellect would have generated the life which would have given birth to our mortal soul.

Admit, the times of discussion, that our beliefs are beliefs and not first truths.

If men manage like this to lower their ideological guard, the time to throw a curious look above the hatred of the neighbour, they will arrive less frequently to slit the throat of their fellow mate for a simple opinion offence.

Nonetheless, whichever the culture which has formed them might be, the majority of people would be happy to put into practice the beliefs of their ideology. They aren't capable either to justify them or to discuss them. There is the role of the theologians, or the ideologists, or the members of the committee of ethics of our sweet France. They are those people there, the big priests, who must organise themselves to compare and attempt to match their ideologies.

It is still more difficult to appreciate mutually the rules of life which lean on forgotten beliefs. You know that it is necessary to make the history of it, that, which quite often, necessitates the contribution of specialists. The historians will come to enlighten the debates.

But I ignored then all that...

« Chapter 8

Chapter 9 - 2nd part »

|

Home

Introduction

All chapiters table

Download the books

Reader's messages

Plus d'informations sur l'ouvrage...

Consultez l'ouvrage en ligne...